Based on the successful Cascadia Sustainability Field School model, the Northern Europe Sustainability Field School attempts to inspire critical reflection and practical action towards sustainability through an engaging field study program. The program begins with a week of classroom instruction, where students are immersed in the literatures of sustainability, regional geography, and field methods, followed by the travel study component itself.

Based on the successful Cascadia Sustainability Field School model, the Northern Europe Sustainability Field School attempts to inspire critical reflection and practical action towards sustainability through an engaging field study program. The program begins with a week of classroom instruction, where students are immersed in the literatures of sustainability, regional geography, and field methods, followed by the travel study component itself.

The program encourages continuous self and group reflection. It balances structure and guidance with self-directed and community-based social learning (Mezirow 2000, Moore 2005, Reed et. al. 2010). Following Shurmer-Smith et al. (2002:166), instructors “facilitate the experience by making suggestions and responding to observations, stating their own point of view without privileging it, setting things straight when they recognized factual errors, but, otherwise, trying to restrain the urge to dictate”.

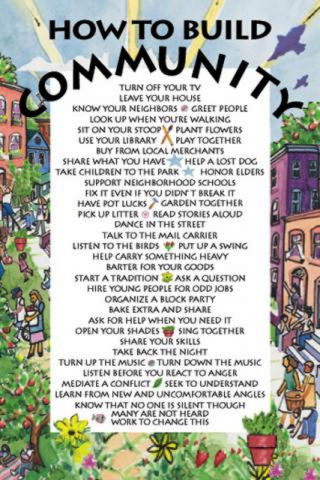

The field school features guided tours, meetings with local actors, community-service projects, hands-on activities, and group reflective “sharing circles”. However, apart from setting the theoretical context in the first week, it does not feature conventional lectures. Instead, students cultivate critical thinking skills through continuous individual and group debate and social interaction (Brookfield 1987, Reed et al. 2010). Each student keeps a detailed field journal, contributes to a multi-media blog and participates in a legacy website and video project. The itinerary and program are carefully designed to afford diverse learning experiences and encounters with multiple (often contrary) perspectives.

We deliver the field program in the spirit of critical pragmatism and transformative learning (see Dewey 1917, Bernstein 2010, Kadlec 2007, Holden et al 2013). Dewey (1917:65) directed academic inquiry away from the stuffy problems of philosophers to practical problems facing communities. The goal of education, according to Dewey (1933), should be to transform the way students see and act with others in the world. Dewey’s (1933) radically democratic pedagogy informs service-based, experiential, transformative and social learning approaches (Giles & Eyler 1994, Mezirow 1997).

Mezirow (2000:214) describes transformative learning as occurring when “we transform our taken-for-granted frames of reference to make them more inclusive, discriminating, open, [changeable], and reflective so that they may generate beliefs and opinions that will prove more true or justified to guide action”. A critical pragmatic approach further emphasizes the interrogation of normalized structures and discourses in capitalist modernity that insidiously reproduce uneven social relations (and could be different) (Kadlec 2007). While critical pragmatism shares this commitment with other critical approaches, it departs from them in its wariness of “ready made answers” that preclude a critical examination of particular arguments given by multiple actors in specific contexts in a world “ineluctably characterized by flux and change” (Kadlec 2007: 12). Critical pragmatists appreciate the de-constructive, polemical, and pedagogical potential of interrogating institutions and processes (surrounding sustainability, for example) as sites of reality construction and contestation (Barnes 2010). To this end, the field school is counseled by Nietzsche (1968 [1895-1896]) to avoid “resting once and for all in any one total view of the world” and, instead, to become enchanted with opposing points of view and to refuse “to be deprived of the stimulus of the enigmatic” (see Figure 3). The field school is thus premised on an anti-essentialist epistemology, ceaseless critical interrogation, interest in the multiple perspectives of various actors constructing or contesting sustainability on the ground in our region and a commitment to creative action arising out of communal inquiry.

Robbins (2004) metaphor of the “hatchet and seed” is useful for communicating the critical pragmatic approach. Students are continuously encouraged to interrogate the dynamics of the devastating “dominant social paradigm” by “cutting and pruning away the stories, methods and policies that create pernicious social and environmental outcomes” with a hatchet while simultaneously cultivating the seeds of creative and practical action (Robbins 2004:12).

Sustainability education often privileges one of the two: robust critical reflection or a pragmatic, action-orientation. Maniates (2013:258) argues that too many sustainability-focused programs privilege applied problem-solving over critical reflection. In so doing, such programs neglect careful consideration of how action fits into “a larger mosaic of political power, cultural transformation, and social change” (Maniates 2013:258). Without nuanced critical reflection, practical action can unintentionally reproduce insidious infrastructures of power.

Conversely, programs may focus exclusively on critical theory while foreclosing outlets for hopeful, practical and creative action (Latour 2004). If the hatchet of deconstruction is wielded without the seed of practical action, students are left as disempowered, indignant spectators. Like Clegg (1999), we believe that simply “teaching subject knowledge falls short of ensuring new practitioners are empowered to question, and potentially improve upon, what they are doing or why” (cited in Smith (2011: 218).

The tone of the field school is thus critically optimistic – eschewing both debilitating pessimism and oblivious optimism about our present condition and future opportunities. We are buoyed by Hawken’s (2009) reflections that, “if you look at the science about what is happening on earth and aren’t pessimistic, you don’t understand the data... but if you meet the people who are working to restore this earth and the lives of the poor, and you aren’t optimistic you haven’t got a pulse.” We intend the field school to inspire students to approach unflinchingly the daunting task of promoting robust, sustainable communities and the cultural-political barriers in the way. We seek to incite a bit of anger, but also hope and commitment to “confronting despair, power and incalculable odds to restore some semblance of grace, justice and beauty in this world” (Hawken 2009).

Meeting with planners, activists, scholars, and others grappling with the daunting social and ecological challenges faced by cities (in this case in Europe) students will be tasked with asking and answering more conditional and qualified questions piercing the who, what, where, when, why and how of sustainability.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|